Some Thoughts of "The Whale"

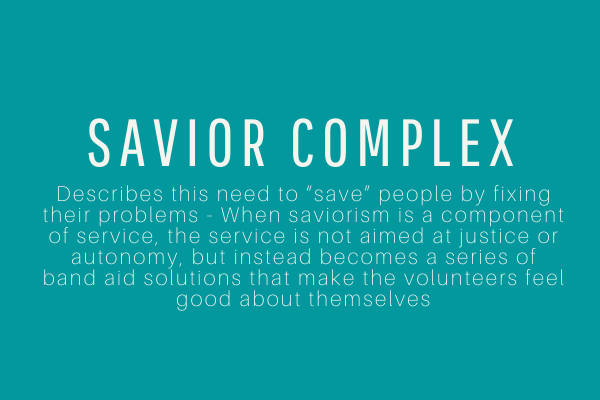

Image courtesy from Boston University Community Service Center

Warning: The article contains spoilers of the movie. CW: Mental illness, death.

I went to the film house with my partner for the movie "The Whale" about a month ago. Despite having a lot of similar mental problems associated with the protagonist, I was deeply touched by the film, but I don't want to extend my words here in all the themes today; just one thing that speaks to me the most is what motivates me to type these down and wish to share with you.

I have seen many comments on social media that it is a film that demeans fat people or devalues gay people because the former mistreat themselves by ingesting too much food to death; the latter implying gay people torture themselves with their past wounds and are incapable of healing from it. The two combined are what the film does - belittle fat and/or gay people, creating inagential representations of these bodies. Some spill their anger on the supporting characters calling them bystanders that let the protagonist die and saying that everyone involved did nothing/inadequate.

By arguing otherwise, I want to revisit a quote from the movie that has been echoing.

"I don't believe that anyone can save anyone."

Sitting on the cinema chair, I heard it; I felt a moment of stillness engulfing my body. Notwithstanding, I felt shocked by the line; I had the same feeling as many others, asking myself many times throughout the movie why no one is helping him. Surely the friend was taking care of him, but not saving him, not calling 911 for him, not forcing him to go to the hospital, only what she did was to bring him food (yes, more food, like he needed to be fed still)... or getting him a wheelchair that he does not need to walk anymore... These are all bad... You are not helping him... He's still dying.

And why do all the characters just let him eat up his agony and leave him to die?

But what if I don't believe that anyone can save anyone?

The feeling of saving resembles the sense of rescuing that stands with being disoriented and deserted in the wilderness; one is strayed. Therefore one needs to be rescued, salvaged from misery, and redirected to the right path. However, the protagonist knows his way; he sits in the middle of the trauma and reanimates it repeatedly; he knows, particularly, what he is doing; that is the right path for him. Eating has become a process of mourning. He is coping; food not only tokenizes his anguish but also touches him year by year, day by day, moment by moment with his grief; food is what heals him, even if it is not a normatively productive sense of healing. Nevertheless, it is what he chose to be healed from. It is his way of reconciling and abreacting with the past and exasperation. It is his way of healing. When everyone has left the show, only food is there to accompany him. That reanimation of the past through the vehicle of eating when no one is around when the space of his home that has become so strange after the passing of his partner stretches the notion of loneliness, longingness, and unwillingness to a degree of extreme; eating is his way of surviving in and fighting against the system. Even if that survival is transient, it is survival. Even if that fight seems so obscure, it is a fight.

Gay people do not need to be saved. Fat people do not need to be saved. Fat gay people do not need to be saved. If they won't heal from the past, it is the past's fault; whatever actions they choose to heal from are valid. What caused the past? Who constructed the past? From when did the past transform into trauma? And why did the past reappear as trauma? IS what one needs to be critical of. Bodies only matter; they do not need to be saved.

I do not believe that anyone can save anyone. We are living, making connections, or perhaps unmaking some connections, respecting, loving, but not saving, coercing, acting superior, or above any.

References

Judith Butler (2011) Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex